Work Camp 10105 GW

Work Camp 10105 GW |

|

|

Location: Radenthein

Type of work: Magnesite factory and mine

Man of Confidence: SSM A.D. Aris, 2821?

Number of Men: 21 approx.

Forename |

Surname |

Rank |

Unit |

POW |

Comments |

| A.D. | Aris | SSM | RAC | 2821 | MOC? also 139/L |

| Norman | Barton | Pte | RAOC | 3199 | Blackburn; also 11088/GW? |

| George | Bodman | Spr | RE | 2761 | also 11088/GW |

| William John | Brotchie | Pte | 2/6 Inf. Bn. | 3814 | Australia; also 27/HV, 10511/GW |

| Edward H. | Calver | Spr | RE | 3069 | Essex |

| Gilbert T. | Campion | Dvr | RASC | 3422 | also 11088/GW |

| ? | Clark | RASC | |||

| Augustine. G. (Gus) | Curtin | Gnr | 1 Cps Ary | 3682 | Australia |

| John H. | Dunham | Dvr | RASC | 2786 | London |

| W.J. | Henderson | Pte | RASC | 2539 | possible |

| ? | Hill | RASC | |||

| Leonard | Kitching | Pte | 4115 | New Zealand; also 11088/GW | |

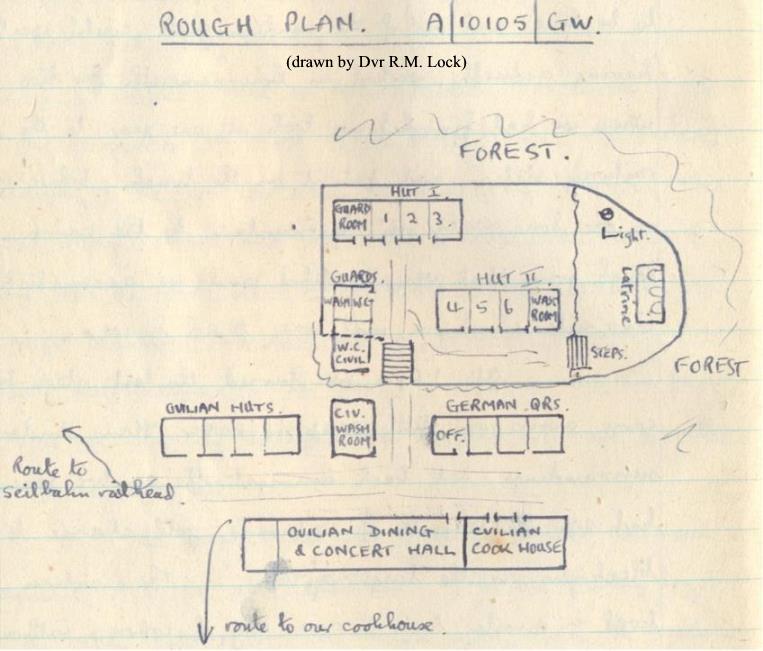

| Reginald Moore | Lock | Dvr | RASC | 3026 | Bornemouth; also 27/HV, 352/GW, 13048/L, 10029/GW, 955/GW |

| Clemence Percy | Moore | Pte | 3474 | New Zealand; also 11088/GW | |

| L.T.H. | Narborough | L/Cpl | RAC | 1198 | possible; transf'd to Stalag 344 |

| John Lewis | Reynolds | Pte | 6 Div., AASC | 3478 | Australia |

| Gordon G. | Rigby | Pte | 258 | New Zealand; also 10030/GW | |

| Joseph | Stafford | L/Cpl | CMP | 2809 | Derbyshire; also 11057/GW |

| 'Blue' | Roddy | Pte | H.Q. 6 Div., AASC | 3537 | Australia |

| Sydney R.B. | Willis | Dvr | RASC | 2789 | Droitwich; also 139/L, 955/GW |

| Leslie | Woodward | Pte | RASC | 3098 | Manchester; also 11078/GW |

Information and photos supplied by Brian Lock, son of Reginald Lock, Matt Pooler, grandson of Sydney Willis, Ken Curtin, son of Gus Curtin, Patricia Rigby, granddaughter of Leslie Woodward and Harry Stafford, son of Joseph Stafford .

Founded in 1908 to mine and process the deposits of magnesite in the mountains above Radenthein, the company still exists as the worldwide corporation RHI AG. Magnesite is an ore from which magnesium oxide can be extracted. This is used in the steel industry as a refractory material in blast furnaces. The factory was and is in Radenthein but the POWs were held near to the magnesite mine in the mountains above. The ore was transported to the factory via an aerial tramway (Seilbahn) operated by the POWs. Parts of the tramway still exist.

|

|

|

|

|

| The Seilbahn (Aerial Tramway) | ||||

This section begins in October 1941. A group of POWs had been transported from Wolfsberg to Stalag 18B (which would later become Stalag 18A/Z at Spittal an der Drau). Despite his short stay in Radenthein, Reginald gives a very detailed account of the day-to-day life of a POW.

Oct 22

First thing in the morning we had a heavy feed of

potato soup and coffee before setting out on that wretched march. In a short

while we had left the town and were winding up

a beautiful gorge by the side

of a rushing torrent. The steep mountainsides were ablaze with the golden

autumnal tints; the blue sky above completed the regal scene that we

could

not appreciate owing to our new boots and heavy loads.

After about an hour’s

march Providence came to our rescue in the shape of two large lorries, with

trailers, belonging to the firm for whom we were going to work. The first

brought bread and coffee and a little later the two of them took the whole lot

of us up to the factory, passing through beautiful lakeland scenery, following

the shores of lovely

Millstättersee on the way. When we saw how far it was we

were very thankful that we did not have to walk all the way after all.

The

firm turned out to be the Ostërr American Magnesit, A.G. Co. at Radenthem. The

big factory lay in the valley but the ore was mined away up in the mountains and

sent

down by an overhead cable railway. The finished product also left the

factory by cable railway leading to a station over on the Spittal railway line.

The first thing we did on arrival was to pile into the nicely decorated works

canteen for a feed. We sat down at little tables with cloths on and bread and

soup was brought to us.

That seemed almost too good to be true and one of the

canteen girls could speak English having actually worked in Bournemouth for two

years! When we had finished we took

all our gear to the cable railway station

and put it on the trucks before starting on the long walk up the mountain to the

camp. It was tough going but very beautiful and we

accomplished the six miles

climb in just over three hours.

At 1.0 p.m. we turned the last steep bend and

came across our little camp in proper Hans Andersen surroundings, set back

amongst the sombre pines; we had seen the warmth of

Autumn’s gold change to

winter’s bleakness on the long way up. The civilian workers lived in similar

huts to ours only, of course, without the inevitable barbed wire. A little

while after arrival we entered the camp and twenty men were put into each room.

There was much more space in those barracks than there was at Zeltweg and each

room had its

own radiator but there were no stoves for cooking. Washing

facilities were as many for the hundred of us as there were for the six hundred

of us at Zeltweg.

Before darkness fell we went up to the rail-head to collect

our gear and then went on parade outside the camp when we got our new jobs

allotted to us for the morning by the

chief engineer. I stepped out with five

others as petrol engine drivers.

Oct 23

Reveille next day

was at 6.0 a.m. and coffee was brought in at 7.0 a.m. We paraded for work at

7.30 a.m. in the newly fallen snow. Then I discovered that the six of us had

been

put on shift work and did not have to start until 6.0 p.m. that evening.

Rather than go to bed again I did a few digging jobs in the camp and the snow

Our own cooks prepared

our meals in an old cookhouse several hundred yards

from the camp, away down in the woods and we could walk in and out of the camp

gates just as we pleased. Apart from

the cold I thought it was a good camp.

After an early tea three of us went up to the cable railway loading shed by 6.0

p.m. and started work. It was not a bad job for a change and we were working

with four friendly

civilians. The job for us was divided into three parts.

The first was to guide the empty skips round to the fillers as they were

released from the endless cable. That was easy but

cold so we changed it

round among the three of us every hour.

The second part was to operate one of

the compressed air fillers which allowed the rock in the hopper above to fall

into the skips. It was surprisingly hard work for the ore was

very heavy.

Also large pieces frequently jammed in the chutes and had to be dislodged by

prodding with long steel rods. Immediately tons of rock roared down like an

avalanche

which indicated a quick move! I was too slow once and lost a little

finger nail in consequence. The stoppage was also caused by the damp, sandy part

of the ore freezing

up in the chutes. There were fourteen of those fillers in

the shed. The third part was to push the loaded trucks round the shed on the

overhead rails to the point where they

clipped on to the moving cable to

start their journey to the factory. Each truck held about half a ton of ore and

there were 250 of them on the line. The

whole apparatus was operated by

gravity alone, only a friction brake being used to stop it. The line was about

seven kilometers in length and the trucks took two hours for the

journey

there and back. The job had the advantage of being under cover as there was so

much snow on the ground.

I finished work at 4.0 a.m. next morning but had

extra food during the night which compensated for the inconvenience of the

shift. The three of us went to and from work

without a guard. That feeling of

freedom was worth a lot.

Oct 24

It seemed strange to have

to sleep during the day time and I got up for dinner but I was surprised when

told to go on the 2.0 p.m. to 10.0 p.m. shift.

Oct 25

I

was still more surprised to have to go to work again at 7.30 a.m. on Saturday,

snow clearing on some of the stages of the mountain face. However it was quite

interesting to

go on up the mountain and see how the ore was obtained from

the various faces. It was very smartly worked out and a surprising amount of

expensive equipment was in use.

Diesel motors and electric trams hauled the

lines of loaded trucks to the electric liftheads to be lowered to the filling

plant at the Seilbahn rail-head. The air was intensely

cold at that height

(6000 feet).

Anyhow Saturday afternoon came at last and I had a lovely hot

shower in the civilian washroom before doing a few odd jobs. The issue food was

pretty poor but the bread

issue was the same as at Zeltweg but when on night

work we got extra soup and coffee.

Oct 27

My shift went

on from 10.0 a.m. until 4.0 p.m. on Monday and some 300 Red Cross parcels came

up in the trucks shortly after we had knocked off. We were pleased to see

them arrive so quickly. We loaded them on a flat sledge and had some difficulty

in getting them down the slippery, snow covered slope to the camp.

Oct 29

By Wednesday I was feeling pretty rough for one boil had

increased to three so I went “sick” and got a couple of days off but next day it

snowed heavily to a depth of about six

inches; most of the lads stayed in as

a consequence. The first batch of mail arrived but once again there was none for

me. During the afternoon I made a pint of custard down

at our cookhouse.

Oct 31

As I felt better on Friday I did a bit of work about

the camp and helped to fetch the rations from the store in the afternoon, which

have considerably improved in quantity

but potatoes still featured highest on

the list.

Nov 1

I went back to work on Saturday morning

at 6.0 a.m. and it was snowing heavily again as we went back to the camp. On

entering the room I was overjoyed to see two cards and a

letter on the table

for me. It was a dramatic moment - what a fine start for the new month! As

arranged some weeks previously, I celebrated to the extent of a tin of

strawberry jam mixed with half a tin of Nestle’s Milk and nearly made myself

sick. When I get my first letter from Ida the other half of the milk goes west

together with a tin of

raspberries. One must celebrate such great events! On

partially recovering from the excitement I had a shower and settled down to read

and re-read the mail before drafting

out replies.

Nov 2

The snow lay about eight inches deep on Sunday morning and it was delightful to

lay in bed until 9.30 a.m. The icicle-fringed windows accentuated the cosiness

within and we

were loath to get up. There were no parades at the week-end so

that we were able to take full advantage of the time off. After copying out my

letters Church and I went

down through the snowy woods to the old cookhouse

and cooked up a packet of oatmeal in a big jam tin. The Sanitator dressed by

boils before I went to the service

which was quite good. The hymns were:-

Fight the good fight

Jesu, lover of my soul

Now the day is over

Nov 3

Monday started my week of night duty at the Seilbahn

and I was supposed to begin at 4.0 p.m. I went up ready to start at that time

but on arrival was told that there was no shift

working that night as the

hoppers were still empty so back I came at the double in case they changed their

minds! Some more mail arrived but there was none for me.

Nov 4

The worst blizzard of the winter set in on Tuesday evening, with a howling wind

which quickly piled the driving snow into deep drifts over three feet deep in

places. I was very

glad to finish at the Seilbahn at 6.0 p.m. and got very

wet floundering back to camp in the dark.

Nov 5

Mr.

Read’s birthday started the official winter season and I spent the morning snow

shovelling on the track up to the Seilbahn. It was such lovely dry snow and

would have

been ideal for tobogganing. How we would have loved to see so much

at home a few years ago but having to work in it took the edge off the thought.

The carts that were still

in use round the colony were all fitted with

runners and used as sledges. During the afternoon our shift went up to the

Seilbahn to help handle tons of cabbages that were

coming up in the trucks.

We had to put them in sacks and I had never seen so many before; truly without

cabbage and potatoes Germany would starve. We worked till 6.0

p.m. on that

job and then got back to the cosy barracks for a good tea as the food had

improved considerably. Our own separate cookhouse had closed down and at that

time

our meals were served from the civilian cookhouse in the camp. The hot

water radiators in the barracks were hot enough to heat up tins of conserve but

they made the air round

the top set of beds too hot at nights.

Nov

6

Only one letter arrived on Thursday - a disappointment. There was

no work owing to a high wind which made work on the exposed mountain stages an

impossibility.

Nov 8

On Friday morning I went out snow

shovelling but felt thoroughly rotten with further boils - one on the neck and

several more on the back. The morning passed somehow, so

beautiful, but at

lunch time I went “sick” once again. I was still feeling bad on Saturday morning

and so did not go to work. I never realised before how very painful boils were.

Nov 9

Sunday was a real day of rest in the warm but how I

longed to get home once again to one of our old Sunday teas followed by service

and a jolly walk home. We had a good

service in the evening after which the

lads in our room (which was the quietest in the camp) had a voluntary discussion

based on a reading from my book “The meaning of

Prayer” by Dr. Fosdick. It

was well worth while too.

Nov 11

During the following

week I got worse and did not go out to work at all. Every night old Ken tried

hard to squeeze the boils out but it was no good and they went on spreading.

The two minutes silence on Armistice Day were observed by the lads out at work.

Nov 13

Thursday dawned dull and warm with a hint of rain in

the air and at 9.0 a.m. five of us together with the interpreter started away

down the long trail to the village to see the

doctor. I set out to enjoy the

walk never doubting that I would be back in camp by nightfall. By 11.30 a.m. we

were in the waiting room and within half an hour I had been

examined and

marked down for return to Stalag for treatment.

From the doctor’s house three

of us went down to the Works Canteen and sat down to quite a decent dinner with

the guard at the same table. The firm supplied us with

travelling rations and

then we settled down to wait for our kit which was being sent down on the

Seilbahn. The weather was still dull and cheerless; the hilltops were

wreathed with cloud and before long it began to rain steadily. During the

afternoon most of the employees in the factory crowded into the canteen to hear

a speech put over

by some big shots dolled up in brown uniforms. The workers

HAD to attend and were not allowed to leave the factory until it was all over.

They did not seem very interested. Our kit

arrived down at 3.0 p.m. but it

was nearer 5.0 p.m. before we managed to scrounge a lift into Spittal, on an old

milk lorry. It was dark when we arrived at the railway station and

we climbed

into an ordinary class III carriage filled with civilians; however the black-out

was such that we were in almost total darkness. The train left at about 7.0 p.m.

and girls

did the ticket inspecting on the journey through Villach to

Klagenfurt which we reached at about 10.0 p.m. We spent the night in the station

waiting room there and had a good

feed from our parcels. I had pineapple and

cream, lemonade, bread and butter with jam before settling down to snooze on the

seats as ten civilians and some soldiers were doing

but my boils would not

let me sleep. However the place was nice and warm.